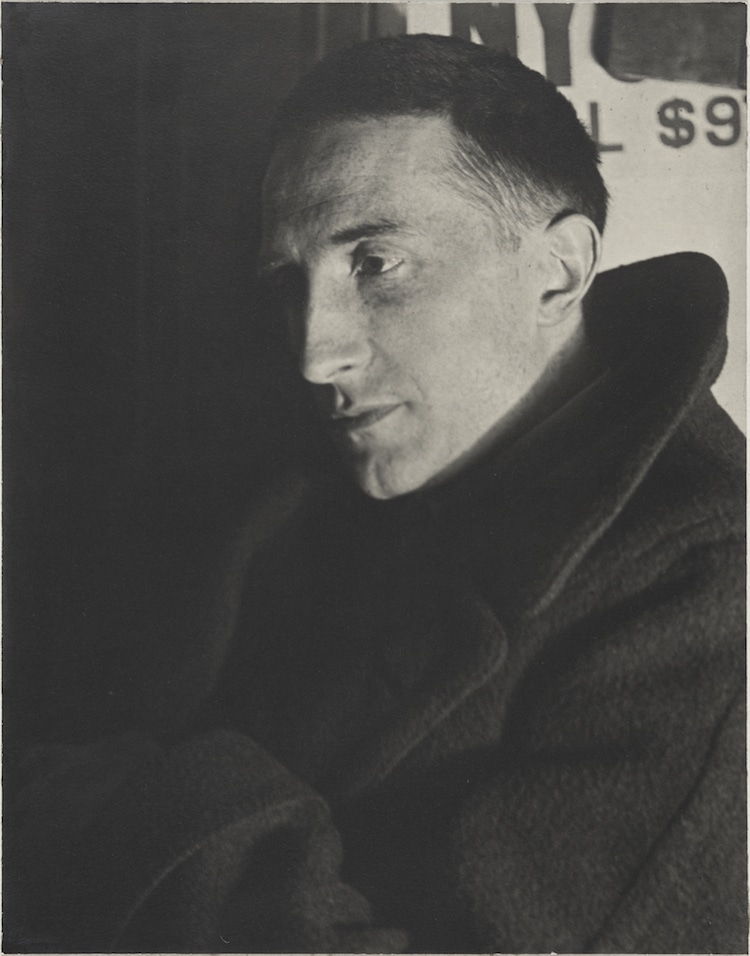

Man Ray, “Portrait of Marcel Duchamp,” gelatine silver print, 1920-21. Photo: Yale University Art Gallery, (Public Domain {PD-US})

Alongside ubiquitous names such as Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol, there is another person who greatly influenced the course of 20th-century art. French-American artist Marcel Duchamp was a pioneering figure in the avant-garde “anti-art” movement known as Dadaism. His unusual approach to art attempted to question the very notion of why it exists and why people cherish it.

While many associate Duchamp with his subversive works like the upside-down urinal entitled Fountain and the Mona Lisa print scribbled with a mustache, there is actually much more to know about the enigmatic figure. Here, we will explore five lesser-known facts about Duchamp to give us a better idea of who this person really was.

Learn all about Dadaism's most famous figure with these five Marcel Duchamp facts.

Full Name | Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp |

Born | July 28, 1887 (Blainville-Crevon, France) |

Died | October 2, 1968 (Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) |

Notable Artwork | Fountain |

Movement | Dadaism |

He came from a creative family.

Marcel Duchamp, “Five-Way Portrait of Marcel Duchamp,” 21 June 1917. Photo: National Portrait Gallery (Public Domain, {PD-US})

Marcel Duchamp was born in Normandy, France, in 1887 to a cultured family. Growing up, he and his siblings participated in a range of activities including painting, chess, and music. His two older brothers and younger sister also became artists. In fact, Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti—his sister—was one of the few female participants of the Dada movement.

He rejected “retinal art.”

Marcel Duchamp, “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” oil on canvas, 1912. Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art (Public Domain, {PD-US})

Although Duchamp's first successful forays in the art world were in painting, that is not where he remained for very long. After his work Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, was criticized for being too Futurist for a Cubist exhibition, he came disillusioned with style groups.

Duchamp's second turning point came after reading Max Stirner's philosophical tract, The Ego and Its Own. This text greatly influenced the way in which the Frenchman approached art. From then on, he rejected visually pleasing paintings in favor of conceptual art that challenged the mind.

He sometimes worked under a pseudonym.

Marcel Duchamp, “Fountain,” 1917. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain, {PD-US})

As a lover of wordplay, Duchamp had several well-known pseudonyms. Fountain, for instance, was signed R. MUTT. The artist explains the reasoning why:

“Mutt comes from Mott Works, the name of a large sanitary equipment manufacturer. But Mott was too close so I altered it to Mutt, after the daily cartoon strip ‘Mutt and Jeff' which appeared at the time, and with which everyone was familiar. Thus, from the start, there was an interplay of Mutt: a fat little funny man, and Jeff: a tall thin man… I wanted any old name. And I added Richard [French slang for money-bags]. That's not a bad name for a pissotière. Get it? The opposite of poverty. But not even that much, just R. MUTT.”

He also had a female pseudonym called Rrose Sélavy (sometimes spelled as Rose Sélavy) which sounds like the French phrase “Eros, ce'st la vie” (meaning “Eros, such is life”), as well as “arroser la vie” (meaning “to make toast to life”). He dressed up as Sélavy for several photos in the 1920s and produced different works of art under the name, including a sculpture and an assemblage.

Duchamp gave up art for chess.

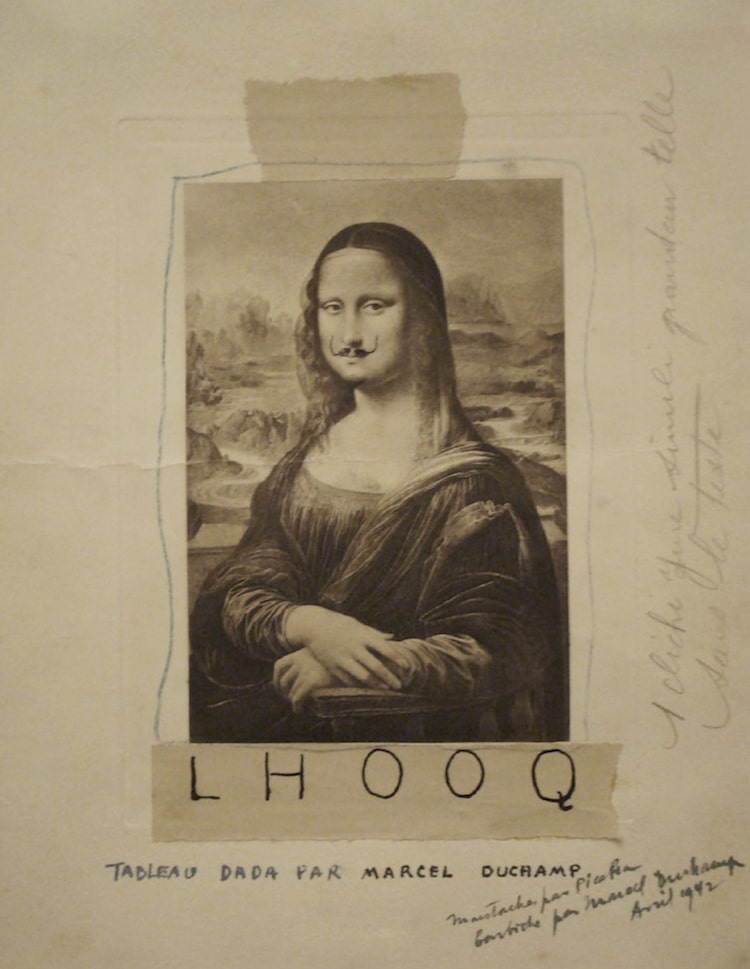

Marcel Duchamp, “L.H.O.O.Q.,” 1919. Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain, {PD-US})

When the artist was 31, he abruptly exited the art world in pursuit of chess, which would be his primary passion for the rest of his life. In 1925, he gained the title of a chess master (the level below grandmaster), and from 1928 to 1933, he participated in the Chess Olympiads.

Eventually, Duchamp took a step back from competitive chess and became a chess journalist. In 1952, he said, “I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art—and much more. it cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position.”

Duchamp secretly worked on his last work of art for almost 25 years.

While many believed Duchamp gave up art decades ago, it was revealed that he had been working on a secret work of art in his apartment from 1946 to 1966. Entitled Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas (French: Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage) this mixed-media assemblage is made of a wooden door, bricks, velvet, wood, leather stretched over an armature of metal, twigs, aluminum, iron, glass, Plexiglas, linoleum, cotton, electric lights, gas lamp (Bec Auer type), motor, etc. The tableau is only visible through a pair of peepholes in a wooden door. It depicts a nude woman lying on a grassy landscape, her face hidden, with one hand holding a gas lamp.

Duchamp requested the work not be seen by the public until after his death. He even left a four-ring binder of illustrated instructions on how to assemble and disassemble the piece.

Today, people can view the piece one at a time at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Related Articles:

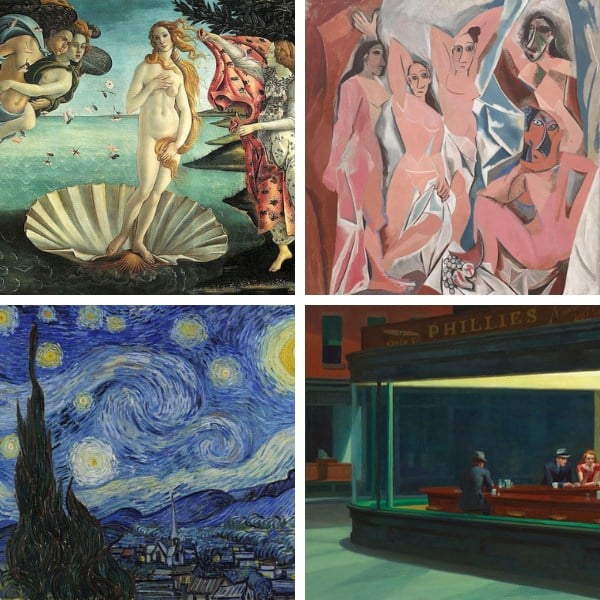

20 Famous Paintings From Western Art History Any Art Lover Should Know

The Origins of Expressionism, an Evocative Movement Inspired by Emotional Experience