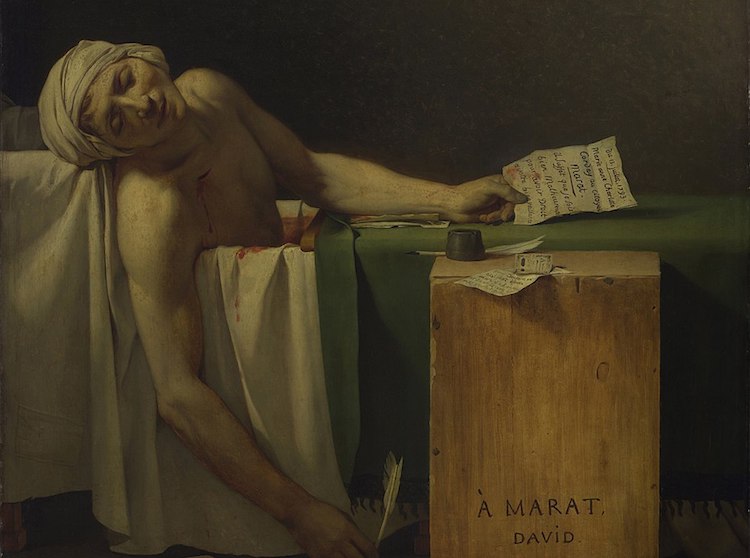

In the middle of the 18th century, French artist Jacques-Louis David pioneered a new genre of painting. Aptly titled Neoclassical, this movement was seen as a revival of the idealized art of Ancient Greece and Rome. Though rendered in a style reminiscent of antiquity, Neoclassical paintings often feature contemporary scenes and subjects. This is the case in many of David's works, including The Death of Marat, one of his most well-known paintings.

The Death of Marat was completed in 1793, four years after the onset of the French Revolution. Like much of David's art created during this decade, The Death of Marat is a politically-charged piece dealing with a major event of the time. In this case, it is the murder of Jean-Paul Marat, a radical political theorist, friend of David, and key figure of the French Revolution.

Title | Death of Marat |

Artist | Jacques-Louis David |

Year | 1793 |

Medium | Oil on canvas |

Size | 64 in × 50 in (162 cm × 128 cm) |

Location | Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (Brussels, Belgium) |

Historical Context

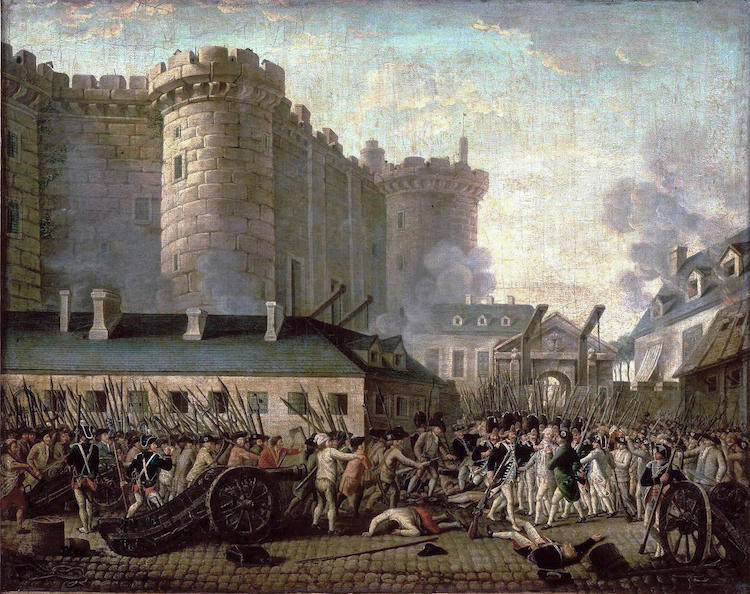

Before analyzing the content of the painting, it's important to understand the context of its creation—namely, the events that led to Marat's death. By the time he died, Marat was deeply involved in the drama of the French Revolution, a period of political and social turmoil that swept across the country from 1789 until the late 1790s.

” Storming of the Bastille and arrest of the Governor M. de Launay, July 14, 1789″ (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

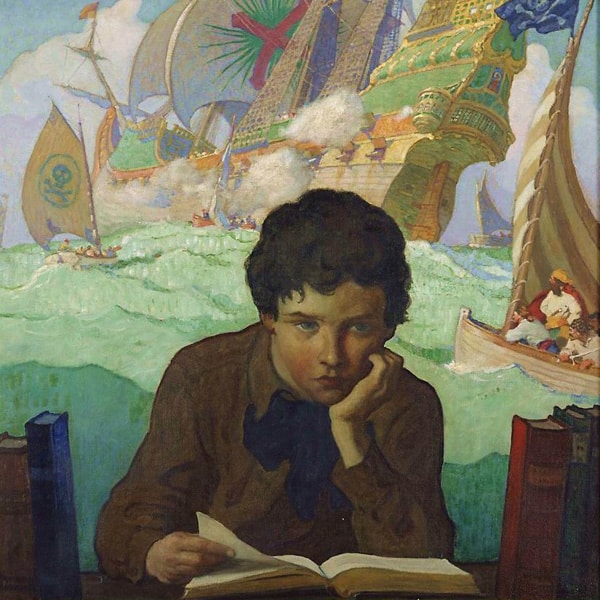

What sparked this movement? Frustrated by the discrepancy between the wealth of the royal family and the highly-taxed and underpaid citizens of France, the people rebelled against the monarchy and demanded change. Revolutionary ideas were also heavily shaped by the Enlightenment, an 18th-century intellectual movement that emphasized individualism. During this time, philosophers, writers, and other intellectuals flocked to Paris, where they discussed, wrote about, and distributed their ideas in the forms of pamphlets, books, and newspapers.

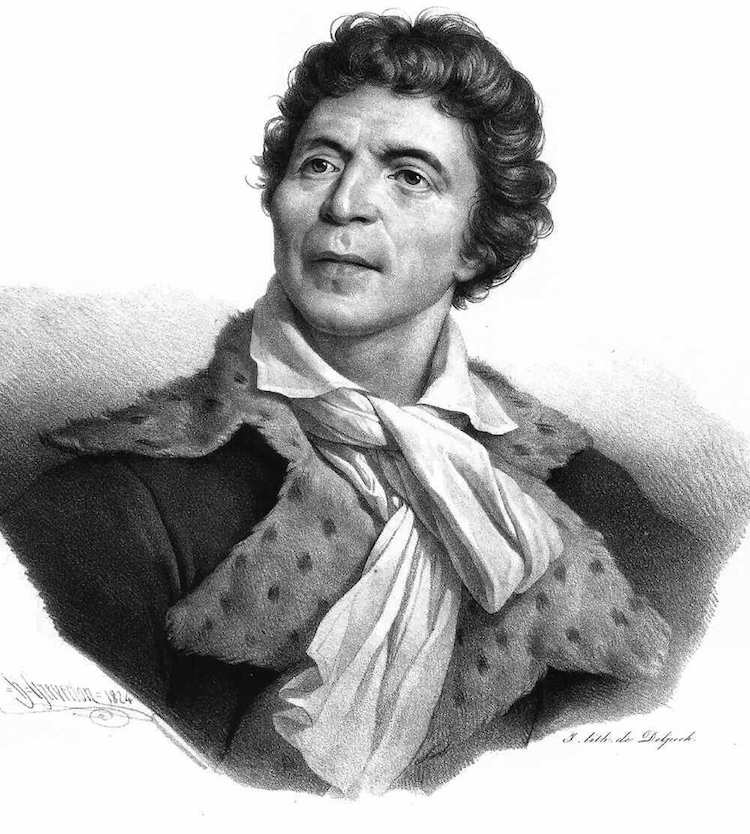

Henri Grevedon and Francois Seraphin Delpech, “Jean-Paul Marat,” 1824 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

As the French Revolution emerged on the heels of the Enlightenment, supporters of the cause adopted and adapted many aspects of the movement—including the use of media to share their ideas. Formerly a doctor and scientist, Jean-Paul Marat abandoned his practices to work as a journalist. In 1789, he founded a newspaper, L'Ami du peuple (“The People's Friend”) to condemn the opponents of the cause—even other revolutionaries.

Politically, Marat's views aligned with the Jacobins, one of the most radical parties to come out of the Revolution. Eventually, he would become the leader of this group, putting him at increased odds with the Girondins, another revolutionary faction Marat regularly attacked from his prominent platform.

As expected, Marat's conspicuous criticism of some of France's most elite individuals and powerful groups made him a major target to adversaries. In 1790, he narrowly escaped arrest; on several occasions through 1792, he was forced into hiding; and, finally, in 1793, he was assassinated in his own home.

Marat's Murder

Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry, “Charlotte Corday,” 1860 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

On July 13, 1793, Marat was writing while in his bathtub. Outfitted with a wooden board, his tub also served as a makeshift desk, as the discomfort of a chronic skin condition often confined him to the bath. As he was working, his wife informed him that he had a visitor named Charlotte Corday. Corday claimed to have confidential information about a group of fugitive Girondins, piquing Marat's interests. Against his wife's wishes, he invited the stranger to sit by his bath so he could write down the names of the offenders.

At the end of the conversation, Corday—an undercover Girondin sympathizer—unexpectedly pulled a 5-inch knife from her dress. She quickly plunged it into Marat's heart and then hid in his home, where she was eventually found and arrested. Marat called for his wife, but nothing could be done; he was dead within seconds.

As both a close friend of Marat and a fellow Jacobin, Jacques-Louis David was tasked with two responsibilities: plan the funeral and paint his death scene.

The Painting

Jacques-Louis David, “The Death of Marat,” 1793 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

David completed The Death of the Marat in his signature Neoclassical style. The piece depicts Marat moments after his murder, as he is shown slumped over his blood-soaked bathtub with quill still in hand.

Like other Neoclassical paintings by David, The Death of the Marat features a perfectly balanced composition; Marat and his bathtub form a horizontal plane in the foreground, which offsets the scene's minimalist backdrop. This arrangement culminates in a theatrical scene reminiscent of a stage production, as a literal spotlight illuminates the main character and a selection of strategically placed props, including his freshly-written list and the bloodied murder weapon, which rests on the floor.

Another Neoclassical characteristic evident in The Death of Marat is an interest in Classical idealism. While both the style and most of the details of the bathtub setup are true to life, David opted to glamorize Marat himself, foregoing a realistic rendering of his visible dermatitis for a glimpse of the blemish-free skin. Along with Marat's Pietà-like positioning, this strategic decision depicts Marat as a flawless martyr.

Legacy

The Death of Marat was very popular with revolutionaries, culminating in the existence of several copies painted by David's pupils as propaganda. However, after the Revolution, the painting fell out of fashion, and was hidden somewhere in France for several years. In the middle of the 19th century, it re-emerged from obscurity and landed a permanent place in the collection of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, where it has remained ever since.

Related Articles:

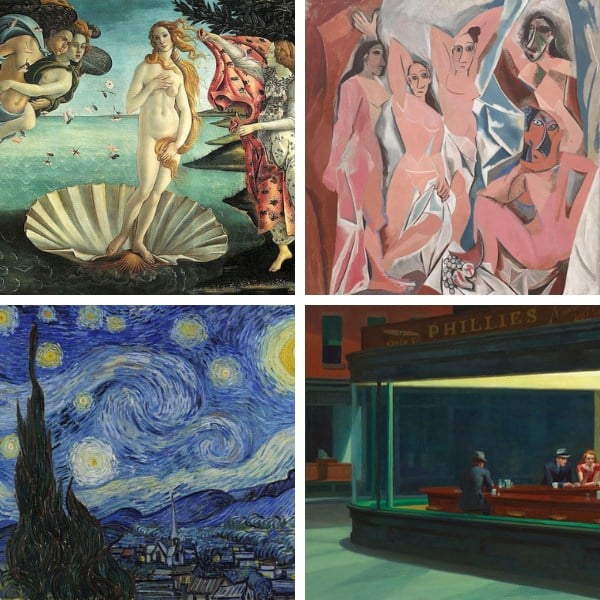

8 Real-Life People Who Became the Stars of Art History’s Most Famous Paintings

Here’s Where 15+ of Art History’s Most Famous Masterpieces Are Located Right Now

Notre-Dame in Art: How the Medieval Cathedral Has Enchanted Artists for Centuries